Falling magnet

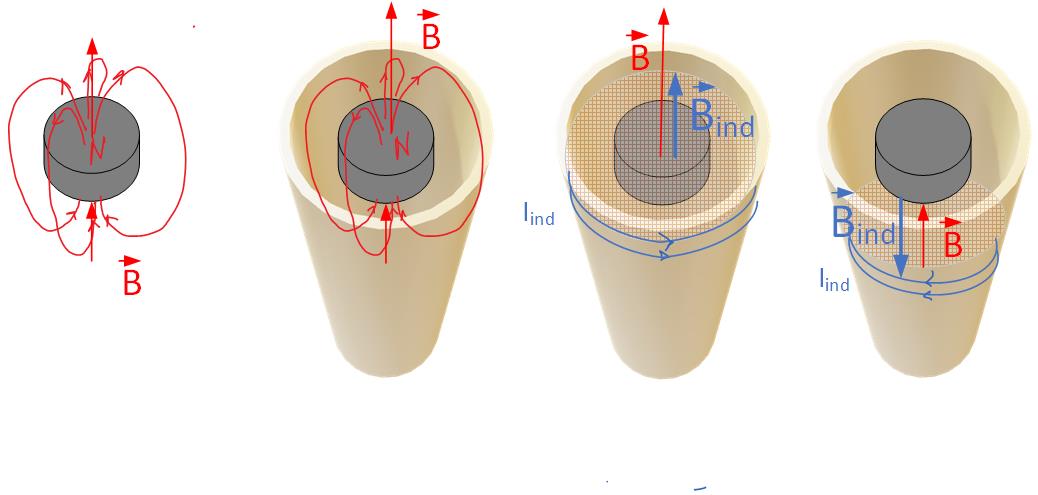

Figure fig:FallingMagnet shows a magnet falling through a copper tube. The magnet will be falling a lot slower than if the tube is not there. We will assume that the magnet falls with its south pole pointing down, as shown in Figure fig:FallingMagnet, to simplify the conceptual explanation, although this assumption is not necessary. We will also use the equivalence of a magnetic field between a magnet and a loop of current. A clockwise current in a loop is equivalent to a magnet whose north pole is pointing down, and vice versa; a counterclockwise current is equivalent to a magnet whose north pole is pointing up.

When the magnet is falling, its north pole’s magnetic field points up in the positive z-direction. The copper tube sees increasing flux underneath the magnet and the decrease of flux above the magnet. Underneath the magnet, a current will form in the tube in such a direction to stop the magnetic field from increasing. In this case, this is the ”down” direction. The current induced in the copper tube will therefore be in a clockwise direction, looking from above. This current has a magnetic field that looks like a magnet with its south pole pointing up, repelling the falling magnet.

Above the magnet, because the magnet is falling, the flux is decreasing, and the induced magnetic field from the current in copper will be in the direction of the magnetic field to prevent it from decreasing. Therefore, the current in copper will flow counterclockwise, looking from above. This current attracts the magnet because its magnetic field looks like a magnet with a south pole pointing down, attracting the falling magnet.

The magnet, therefore, slows down when falling in a copper tube.