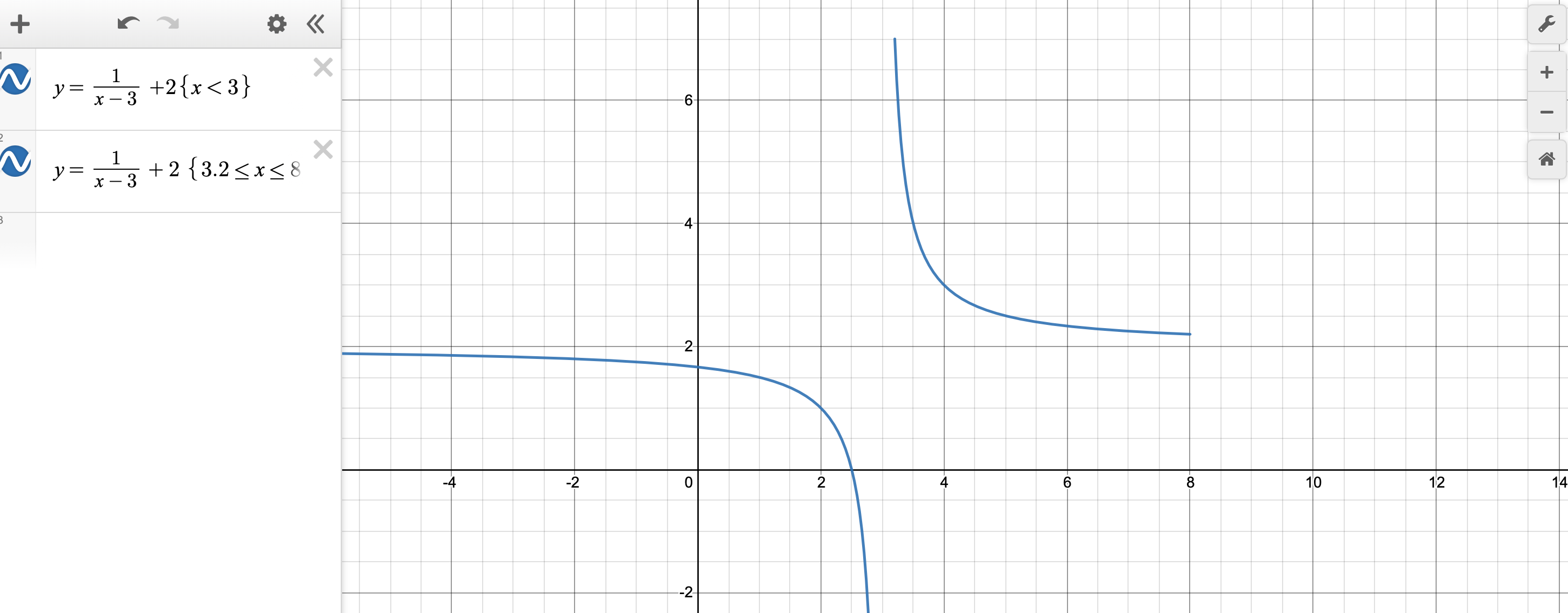

- The graph above has points with -coordinates greater than . True False

- The graph above has points with -coordinates less than . True False

- The graph above has points with -coordinates greater than . True False

- The graph above has points with -coordinates less than . True False

communication

Rigor

What is Rigor in a Mathematics Classroom?

Rigor is when students use mathematical language to communicate effectively and to describe their reasoning with clarity and precision. Students make understood “How do we know we have accounted for everything?”

Rigor is one of the main threads in this course along with function structure. It will

take a lot of communication back and forth to learn how to present rigorous

explanations.

We have already commented that graphs are inherently inaccurate, so they might seem an odd place to introduce rigor. On the other hand, we have noted that graphs are communcation tools. This makes them an easy entrance to the ideas of rigor. We can begin by using auxillary graph symbols to clarify our graphical communication. Their presence and absence communicate information about the function.

Endpoints

Points are dimensionless objects. They are too small to actually see. When we draw a graph, the thickness of the pencil or pen is already an exaggeration of the underlying points and makes the endpoints a mystery. How would you tell if the very last point of a curve was included or not? Therefore, we exaggerate even more for the endpoints, so that the reader immediately understands whether or not they are plotted.

We use big solid dots (blobs, discs) to illustrate an endpoint is a part of the drawing. We use big hollow dots (circles) when the actual last point is not included.

In the graph on the left, it is difficult to tell if the endpoints are included or not. The graph on the right makes this clear.

The big exaggerated dots are just for the single endpoints. The curve on the right does not actually include a circle as part of the curve. That circle is an exaggerated single hollow dot indicating that the point is not part of the curve.

Arrows

When we use graphs to define functions, we need to communicate the domain. This is difficult when the domain is large, such as . The paper we draw on is only inches wide. So, we include several additional graph symbols to help the reader understand what is happening out of view.

Arrows at the ends of curves signal that the curve continues its current pattern.

In the graph on the left, it is difficult to decide if the domain is the interval or not. The graph on the right makes this clear.

Here, the arrow tells the reader that the curve continues its current linear pattern indefinitely to the right. The domain is .

Asymptotes

Arrows at the ends of curves signal that the curve continues with its current pattern. However, this may not not be enough. Many functions have curves that continue moving down and to the right, however, their movement has a boundary. We use dashed lines to indicate that a curve is approaching this line pattern.

The arrows tell the reader that the curve continues its current pattern, for example the right piece of the curve continues to move up and to the left. The dashed vertical asymptote tells us that the leftward movement does not go past the line . The curve continues to go up indefinitely while getting closer and closer to the asymptote, without hitting the asymptote.

This tells us that the function becomes unbounded as you get closer to in the

domain.

Horizontal asymptotes give similar information. The function graphed below gets closer to the value of as the values of the domain get bigger. Unlike with vertical asymptotes, the graph of a function can oscillate back-and-forth across a horizontal asymptote.

The values of the function, , get closer (or approach) as we move through the

domain, heading to infinity.

And, of course, we have algebraic notation to communicate this thought.

This “limit notation” is our algebraic way of communicating that the function approaches the value as the domain values become unbounded positively. More on limit notation later in the course.

Ellipsis

Sometimes an arrow at the end of the curve may give the wrong impression.

If the pattern involves some kind of repeated (periodic) shape, then ellipses may be used.

A graph is a communication tool. We already know that the accuracy has

limitations. There are also other limitations that we must deal with. To that end,

a nice graph displays other symbols besides just the points. These other

graphical features help the reader understand the thoughts of the drawer.

Missing Symbols

All of these graphical symbols help the reader understand the graph. When the symbols are not drawn, then we know the author of the graph does not want us to interpret the graph in that way.

- If there is no horizontal asymptote, then we should not read that the graph is leveling off and becoming horizontal.

- If there are no ellipses, then we should not assume the pattern repeats.

- If there is no arrow, then we should not assume the pattern continues.

- If there are no solid or hollow endpoints, then we need to question the drawer.

The auxillary pieces drawn on a graph give us information and their absence gives us information as well.

Technology

We are humans communicating to other humans, which is why we take care to create readable and informative graphs. Technology does not have this desire.

When working with technology, we have to accept that it is a machine giving us what

it is programmed to give. We must interpret correctly.

When we make our own graphs, then we can hold ourselves to a higher standard.

ooooo=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=ooOoo=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=ooooo

more examples can be found by following this link

More Examples of Graphical Communication