We’ve seen how to express points in using Cartesian coordinates and using cylindrical coordinates. We’ll now introduce an alternative to cylindrical coordinates, called spherical coordinates. Spherical coordinates are also used to describe points and regions in , and they can be thought of as an alternative extension of polar coordinates.

Spherical coordinates

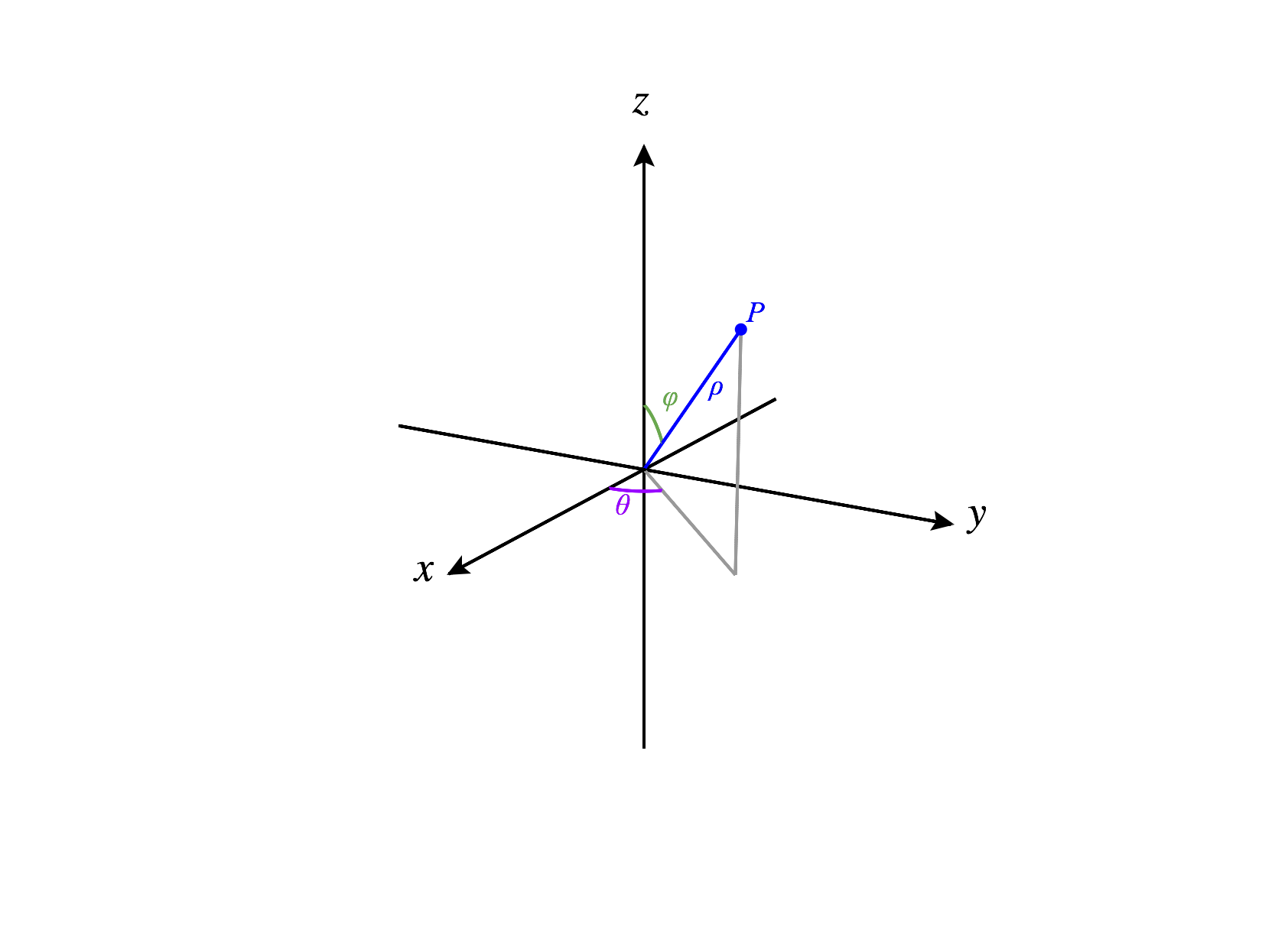

Given a point in , we’ll write in spherical coordinates as . Imagine drawing a line segment from the origin to . Here, is the length of the segment, which is also the distance between and the origin. The second coordinate, , is angle between the positive -axis and the projection of the segment onto the -plane. The third coordinate, , is the angle between the segment and the positive -axis.

Note that in spherical coordinates is the same as in cylindrical coordinates.

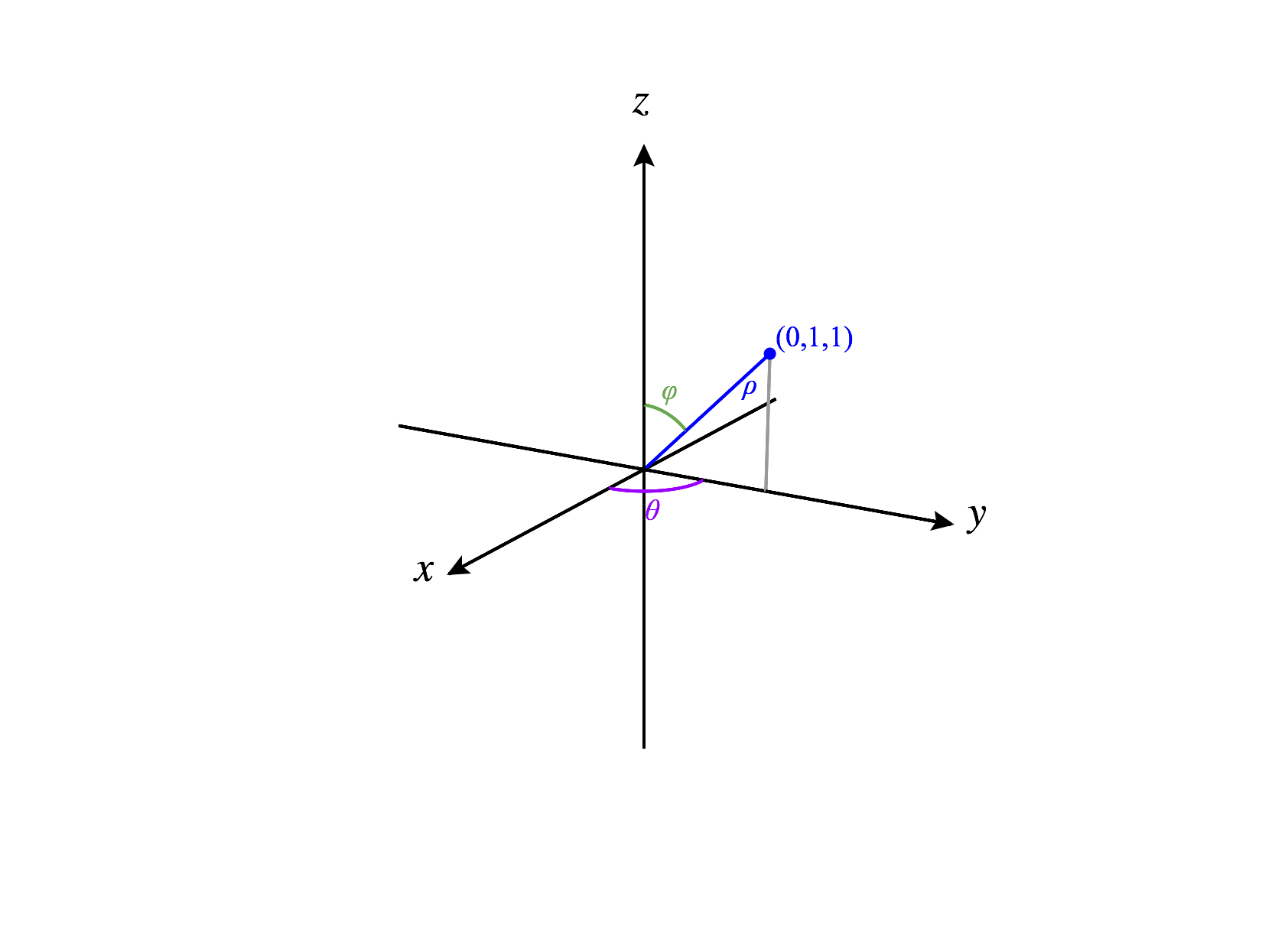

The distance between and the origin is so .

The angle between the positive -axis and the projection of onto the -plane is (in radians), so .

The angle between and the positive -axis is (in radians), so .

Thus we can write in spherical coordinates as .

Although we will be consistent with our definitions of and as above, it’s important to know that some people reverse the roles of and . This is particularly common among physicists.

Uniqueness

As with polar and cylindrical coordinates, there are issues of uniqueness with spherical coordinates that we do not encounter in Cartesian coordinates.

Let’s take for the example the point , written in Cartesian coordinates. We’ve seen the most typical way to write this point in spherical coordinates, as . However, we could also write this as , , or even .

Because of this issue, we’ll commonly use the restrictions

when working with spherical coordinates in order to improve the uniqueness situation. Unfortunately, there are still multiple ways to represent the origin in spherical coordinates.

You may use this applet to experiment with how the different coordinates change a point written in spherical coordinates.

Constant-Coordinate Surfaces

As we did with cylindrical coordinates, we’ll see what happens when we set each of the coordinates to be constant. Throughout this exploration, we’ll use the restrictions , , and .

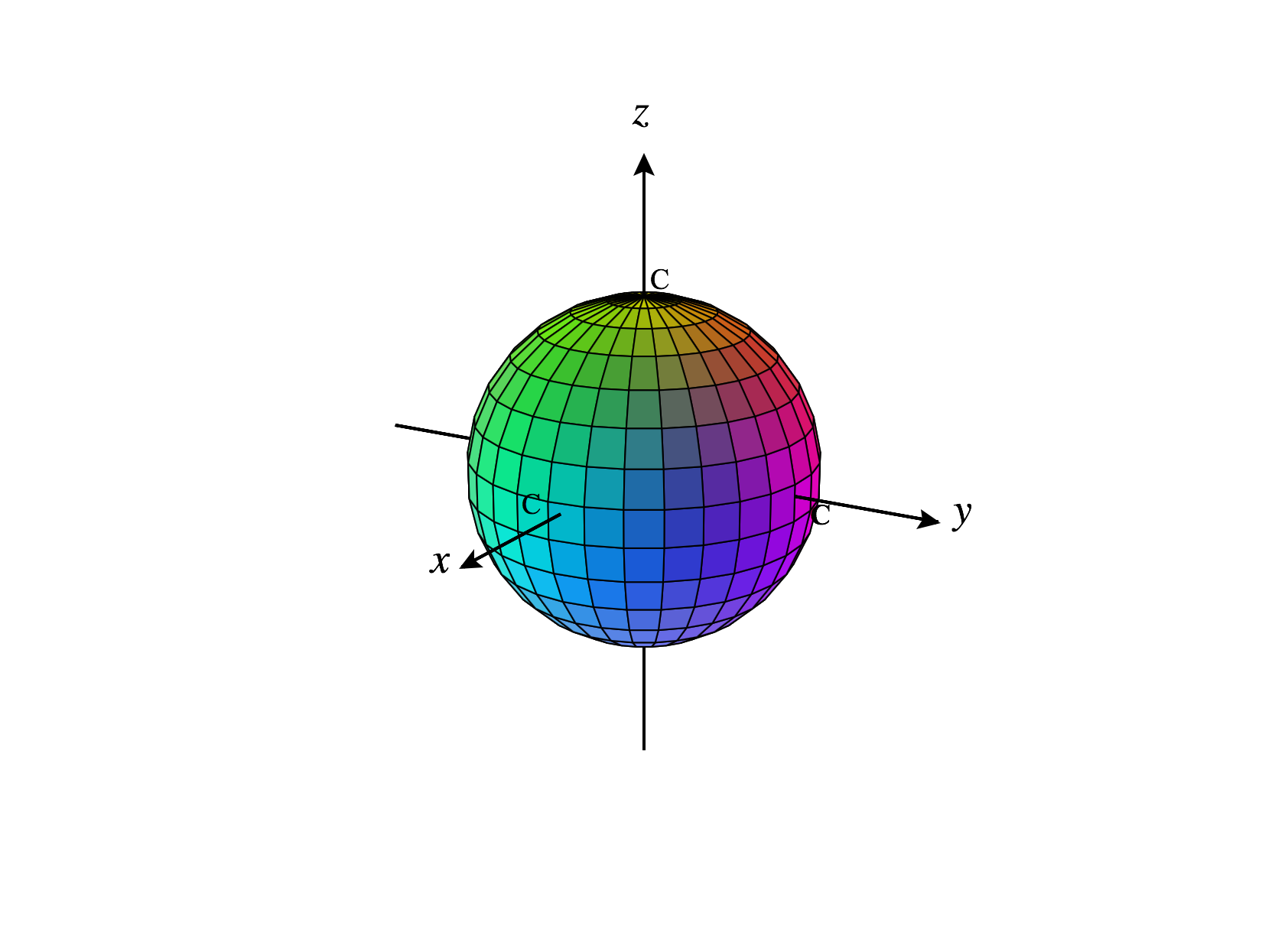

Consider the set of points , where is constant. This means that the distance between the origin and any such point is . Varying the angles and gives us all such points, which make a sphere of radius .

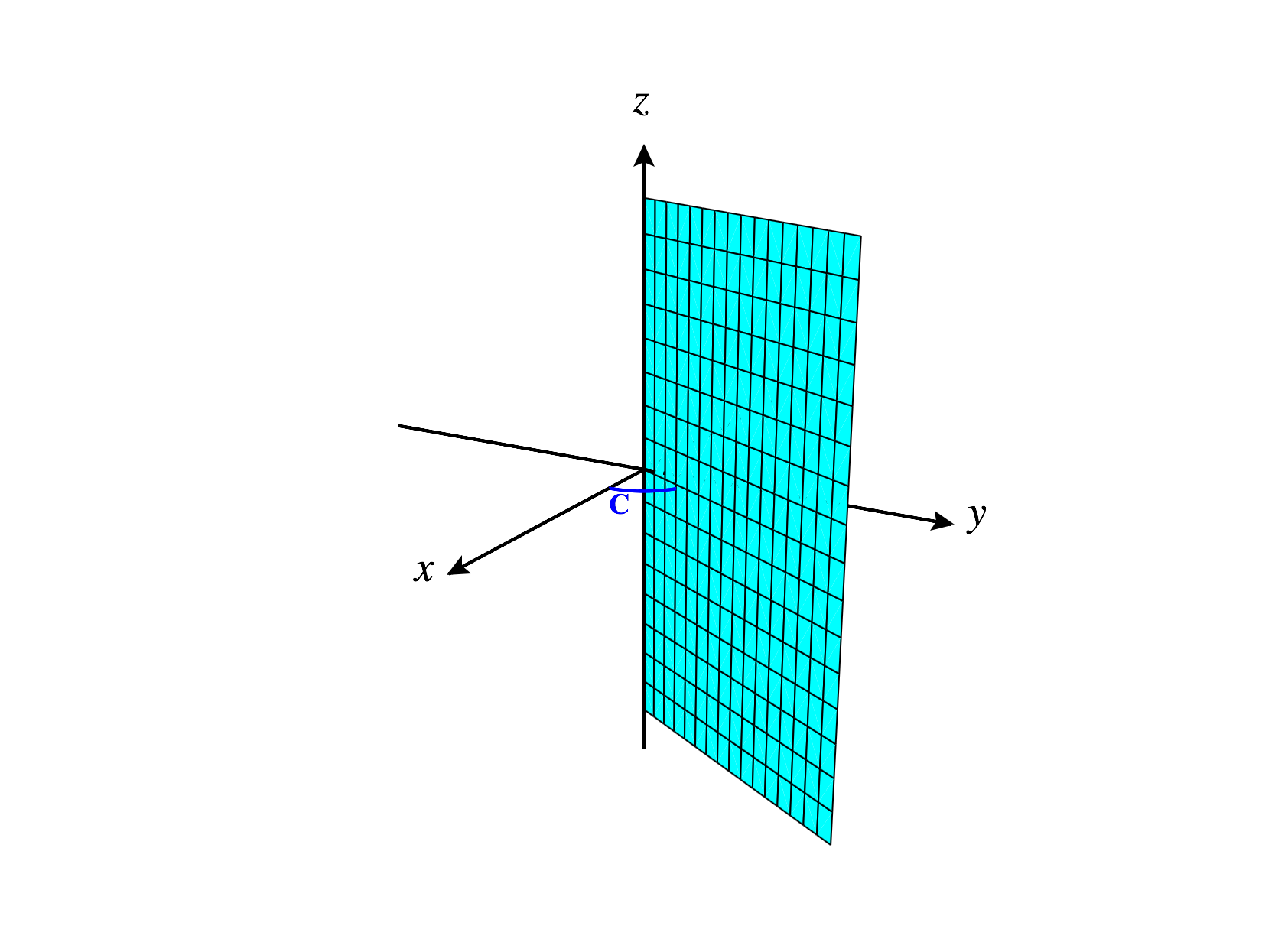

Now, consider the set of points , where is constant. This means that the projection of any such point onto the -plane will make an angle with the positive -axis. Varying gives us points at various distances from the origin, and varying gives us points making various angles with the positive -axis. With the restrictions and , we obtain a half plane, as below.

Notice that if we relaxed the restrictions on and , we could obtain the entire plane.

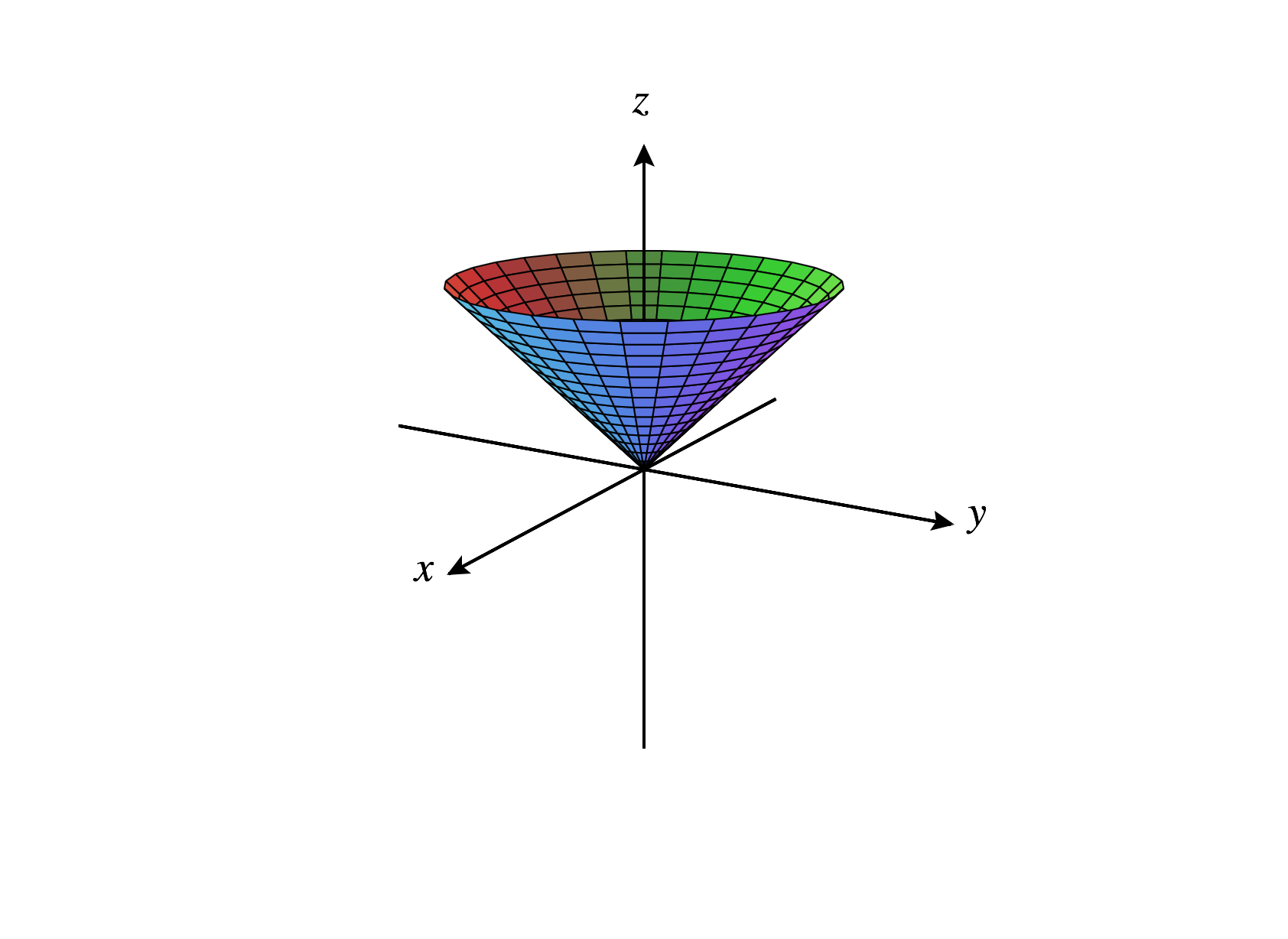

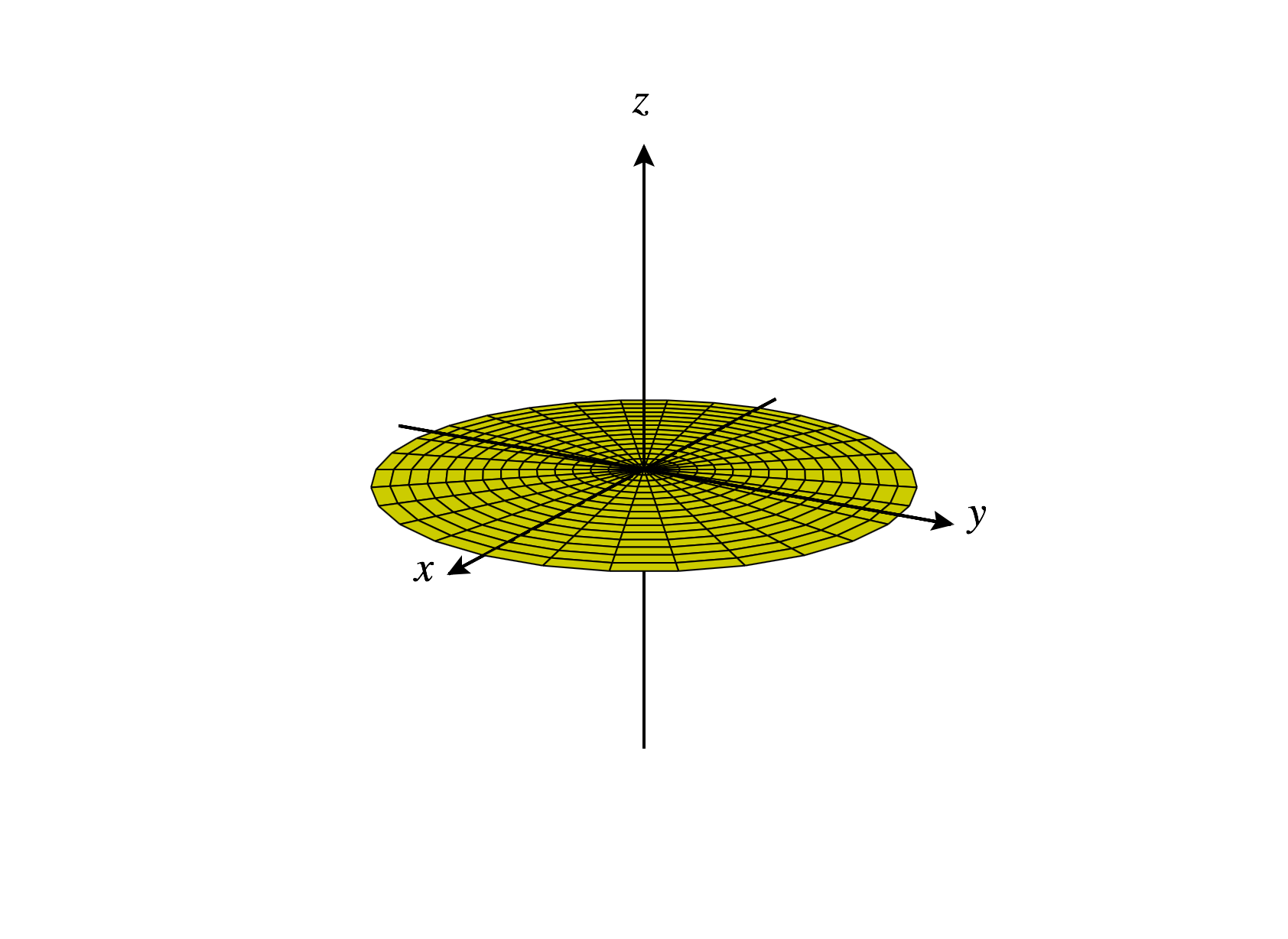

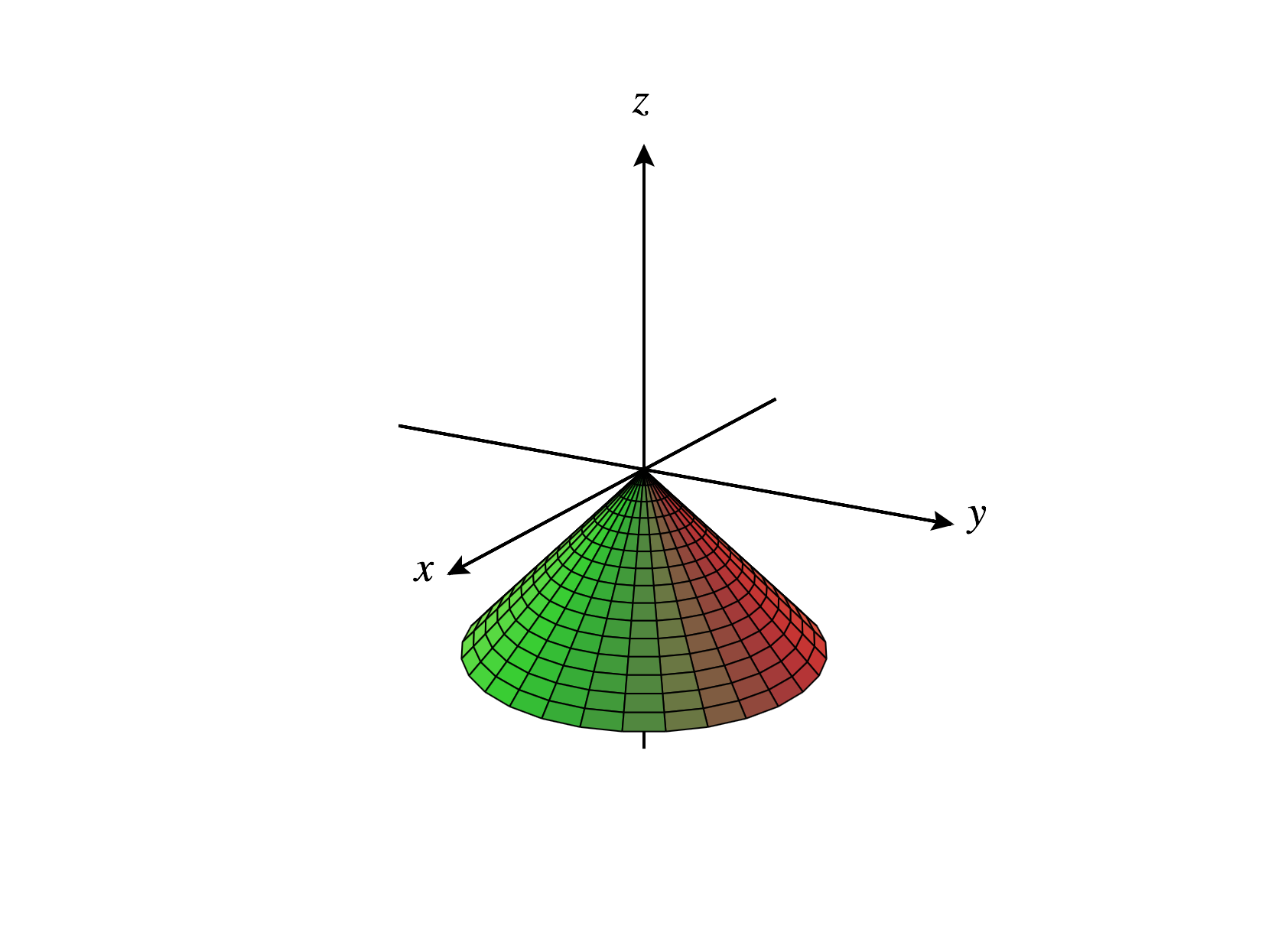

Finally, we consider the set of points , where is constant. This means that every such point has an angle with the positive -axis. Varying and , with the restriction , we get the surfaces below, depending on if , , or .

For ,

For ,

For ,

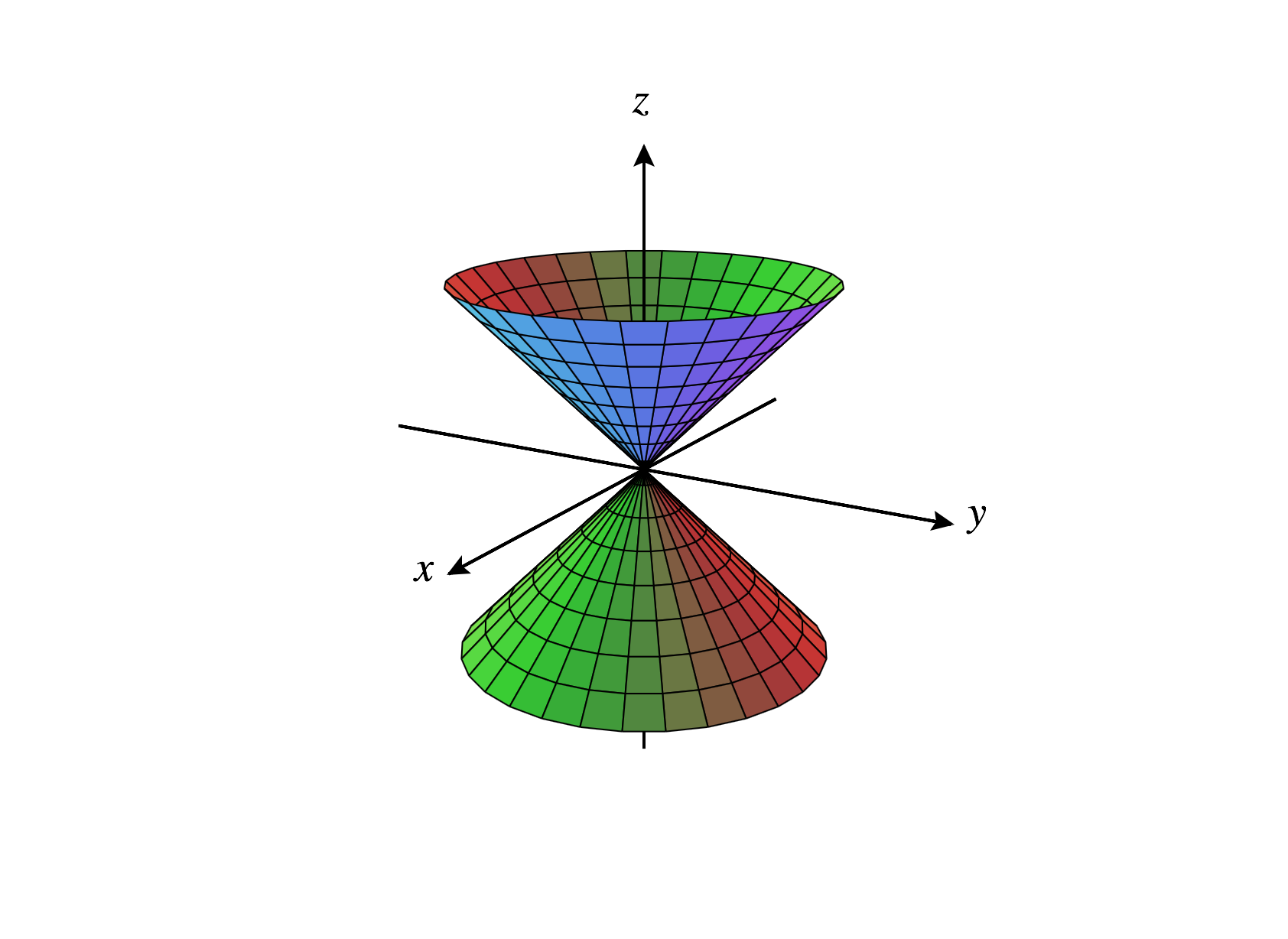

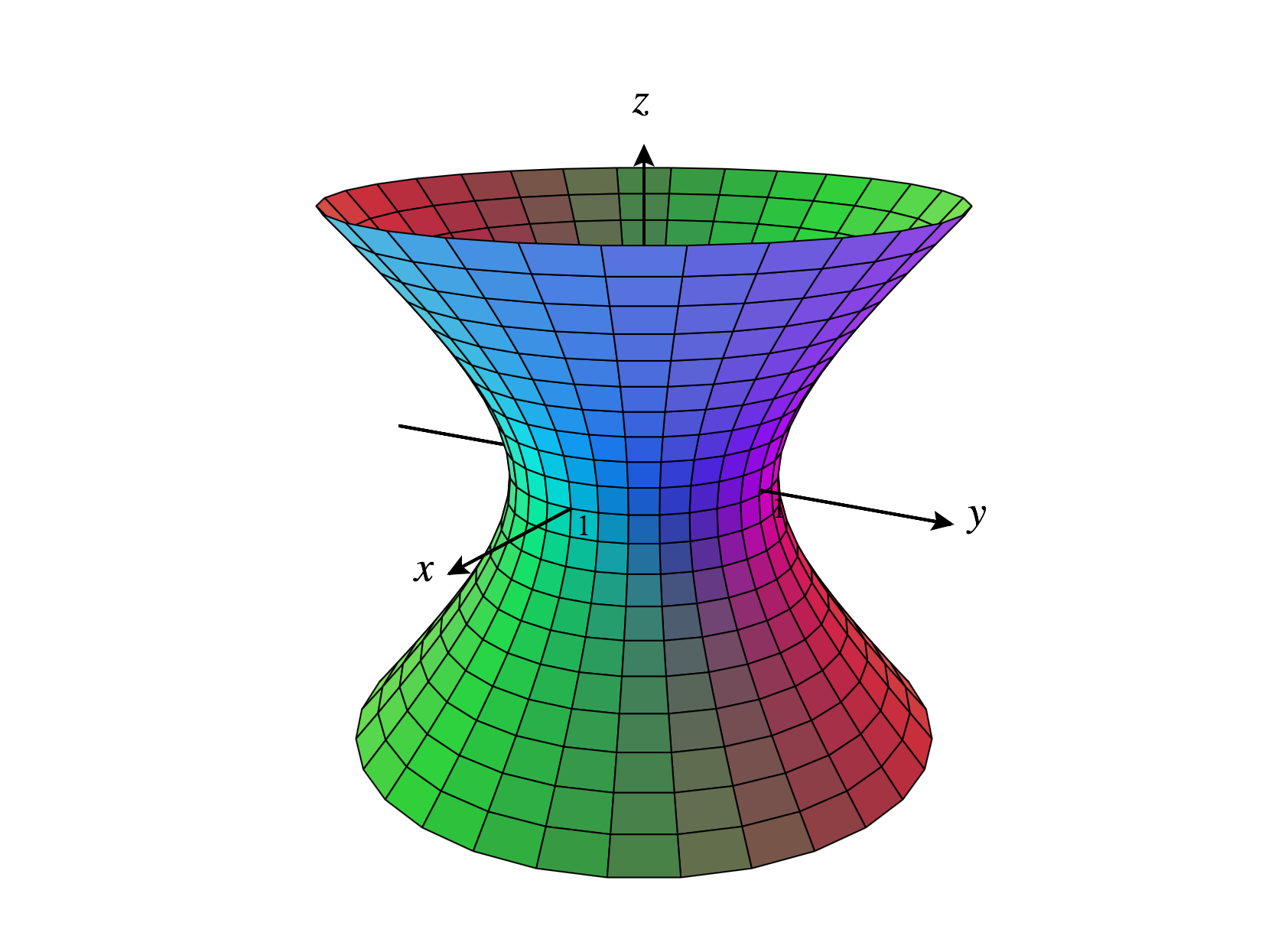

Looking at the surfaces when or , we would commonly call these surfaces “cones.” However, in most mathematics, “cone” is more commonly used to describe the surface below, which you might call a double cone.

Note that if you relax the restriction , you’ll get the (double) cone above when .

It may seem strange that mathematicians prefer this double cone to the seemingly simpler cones that you’re used to. However, it turns out that the double cone is easier to describe algebraically.

You can use this applet to see what happens when you vary the value of the constant for each of the constant-coordinate surfaces above.

Converting Between Spherical and Cartesian Coordinates

When converting between spherical coordinates and Cartesian coordinates, it can be useful to use the following equations, which describe the relationship between the two coordinate systems.

Making the substitutions , , and , we have We can factor out of the first two terms and obtain Recalling that , we can simplify this to Recalling the double angle formula , we can simplify this to

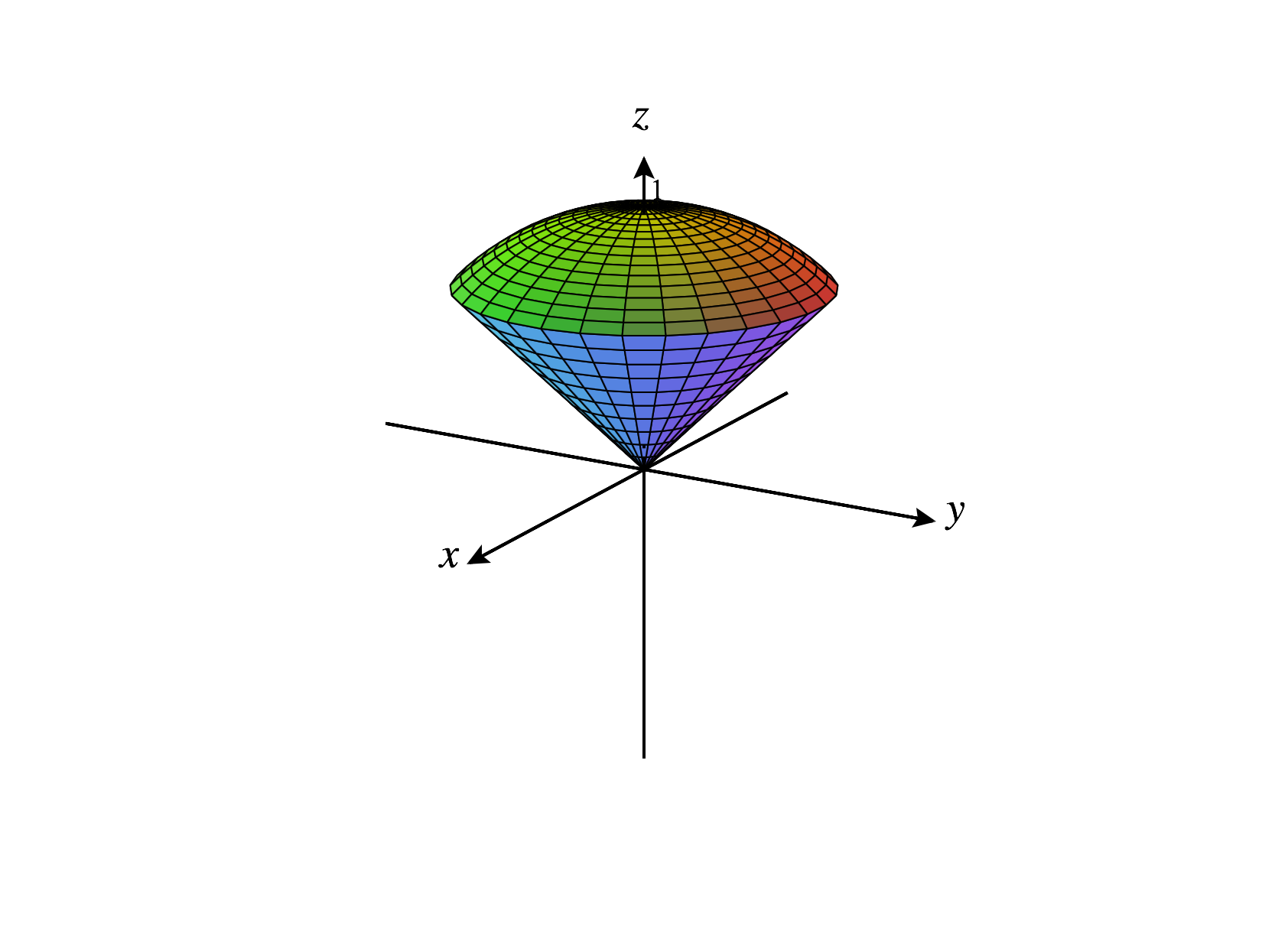

The condition means that we’ll have only points within distance of the origin. The condition means that we’ll have only points within angle from the -axis. Putting these conditions together, we have the solid “ice-cream cone” region sketched below.

What type of shape is this?

Images were generated using CalcPlot3D.