Green’s Theorem is a fundamental theorem of calculus.

| Function | Example | Derivative | Interpretation |

| explicit curve | slope of the tangent line | ||

| vector-valued function | tangent vector | ||

| explicit surface | the vector that points in the initial direction of greatest increase of | ||

| implicit curve (level curve) | gradient vectors are orthogonal to level sets | ||

In this section we will learn the fundamental derivative for two-dimensional vector fields, as well as a new fundamental theorem of calculus.

The curl of a vector field

Calculus has taught us that knowing the derivative of a function can tell us important information about the function. In a similar way we have seen that if we wish to understand a function of several variables , then the gradient, , contains similar useful information. If you have a vector field we now ask: “what is the natural analogue of a derivative in this setting?” When the vector field is two or three-dimensional, the curl is the analogue of the derivative that we are looking for:

Other authors sometimes use the notation for the scalar curl of a two-dimensional vector field , and for the curl of a three-dimensional vector field .

Now for something you’ve seen before, but in a different form.

What does the curl measure?

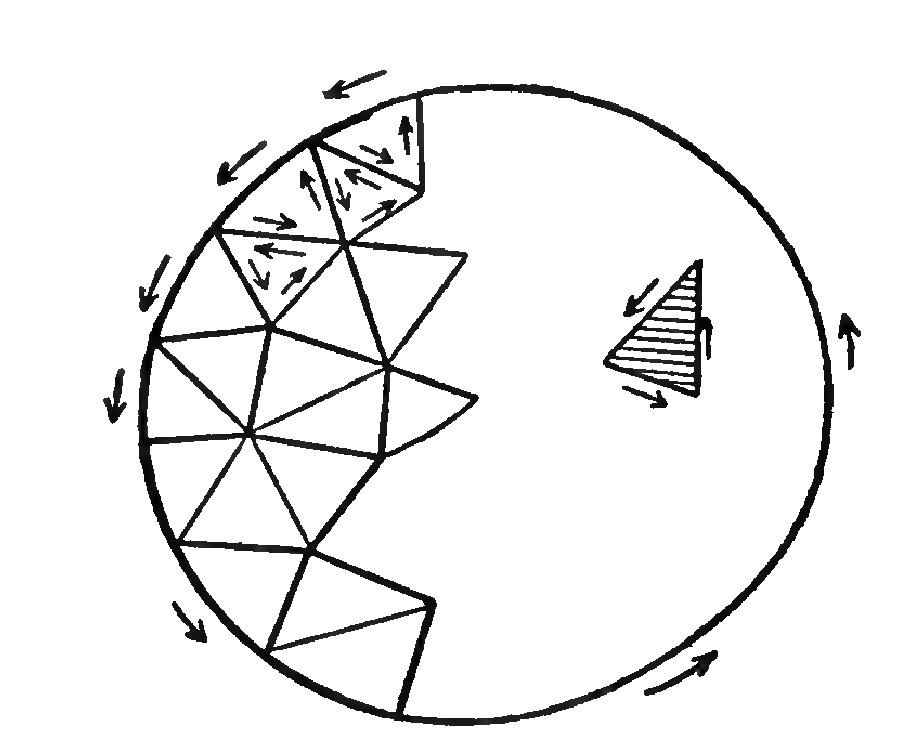

The curl of a vector field measures the rate that the direction of field vectors “twist” as and change. Imagine the vectors in a vector field as representing the current of a river. A positive curl at a point tells you that a “beach-ball” floating at the point would be rotating in a counterclockwise direction. A negative curl at a point tells you that a “beach-ball” floating at the point would be rotating in a clockwise direction. Zero curl means that the “beach-ball” would not be rotating. Below we see our “beach-ball” with two field vectors. If

In essence, the scalar curl measures how the magnitude of the field vectors change as you move to the right, in a direction perpendicular to the direction of the field vectors:

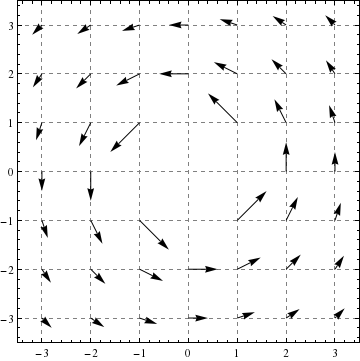

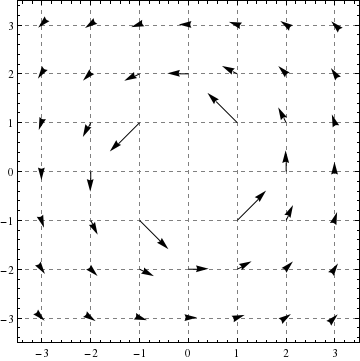

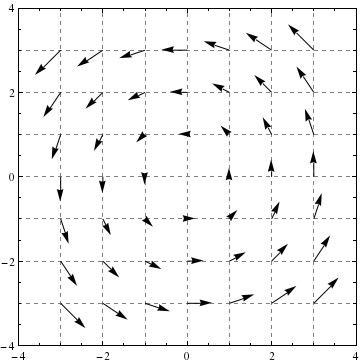

In our next example, we see a field that has local rotation (nonzero curl) but does not have global rotation.

Now we’ll show you a field that has global rotation but no local rotation!

Finally, we’ll show you a field that has global rotation with local rotation in the opposite direction!

Curl in three dimensions

In this section we introduce curl in three dimensions. You already know how to compute it:

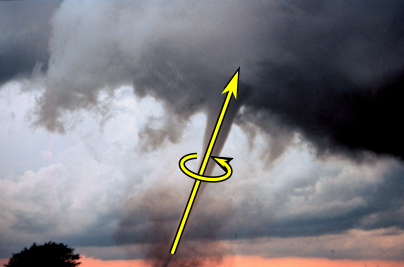

What does it mean? Well first of all, in three dimensions, curl is a vector. It points along the axis of rotation for a vector field. You should think of a tornado:

At this point we only know how to take the derivative (via the curl) of a vector field of two or three dimensions. You can take another course to learn more about derivatives of -dimensional vector fields.

A new fundamental theorem of calculus

Recall that a fundamental theorem of calculus says something like:

To compute a certain sort of integral over a region, we may do a computation on the boundary of the region that involves one fewer integrations.

In the single variable case we have:

The upshot is that we were able to use Green’s Theorem to transform a tedious integral into a trivial one.

How is Green’s Theorem a fundamental theorem of calculus? Well consider this:

Strategy for evaluating line integrals

At this point we have three ways to evaluating two-dimensional line integrals:

- Direct computation.

- The Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals.

- Green’s Theorem.

How do you know which method to use? Here are some rules of thumb.

Identify the field With line integrals, we must have a vector field. You must identify this vector field.

Compute the scalar curl of the field If the scalar curl is zero, then the field is a gradient field. If the scalar curl is “simple” then proceed on, and you might want to use Green’s Theorem.

Is the boundary a closed curve? If the field is a gradient field and the curve is closed, then the integral is zero (by both the Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals and Green’s Theorem).

If the boundary is not a closed curve and the curl is not zero, you must use direct computation.

If the curl is simple and the boundary is a closed curve, then maybe use Green’s Theorem.

The shape of things to come

Recalling that is the set of differentiable functions from to where all of the derivatives are continuous, we can make the following “chain” of derivatives:

Moreover, by the Clairaut gradient test, the scalar curl of the gradient vector is zero. Given a function , we can follow through the chain to see what happens: