Problems about operations and algorithms.

Explain what it means for an operation to be

associative. Give some relevant and

revealing examples and non-examples.

An operation is

associative if for all values

of , , and . Addition of numbers is associative, as is multiplication. Subtraction and

division are not.

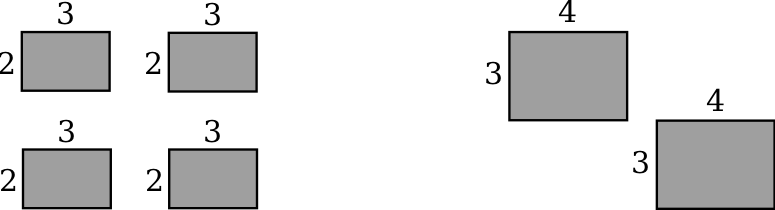

Consider the following pictures:

Jesse claims that these pictures represent and .

-

(a)

- Is Jesse’s claim correct?

Yes. No. Not enough information.

-

(b)

- Explain your reasoning.

Jesse is correct. The picture on the left is copies of ,

and the picture on the right is copies of .

-

(c)

- Do Jesse’s pictures show why multiplication is associative?

Yes. No. Not

enough information.

-

(d)

- If so, explain why. If not, draw new pictures representing and that do show

why multiplication is associative.

We can compute that in both cases the total

area is , but that does not explain

why they are the same. For that, imagine the

volume of a rectangular box measuring by by . Slicing the layers different

ways can explain associativity.

Explain what it means for an operation to be

commutative. Give some relevant and

revealing examples and non-examples.

An operation is

commutative if for all

values of and . Addition of numbers is commutative, as is multiplication. Subtraction

and division are not.

Explain what it means for an operation to

distribute over another operation .

An

operation

distributes over an operation if and .

Give some relevant and revealing examples and non-examples.

Multiplication

distributes over addition because and . But exponentiation does not distribute over

addition because .

Explain what it means for an operation to be

closed on a set of numbers.

A set is

closed under an operation if for all and in the set, and are also in the

set.

Give some relevant and revealing examples and non-examples.

The counting

numbers are closed under addition and also under multiplication but not under

subtraction or division. The set of even numbers (including and negatives) are

closed under addition, subtraction, and multiplication. The odd numbers, in

contrast, are closed under multiplication but not under addition and not under

subtraction.

Sometimes multiplication is described as

repeated addition. Does this explain why

multiplication is commutative? If so give the explanation. If not, give another

description of multiplication that does explain why it is commutative.

Repeated

addition by itself does not explain

why multiplication is commutative. Organize the

repeated addition into an array, interpreting as, say, rows by columns. Rotate the

array , and the array becomes rows by columns, or , which must have the

same number of objects. Essentially the same reasoning works with an area

model.

In beginning algebra, simplifying expressions often involves

collecting like terms. But

why does this work? Well, the expression is equivalent to by the

commutativeassociativedistributive

property. And then it is clear that .

In a warehouse you obtain discount but you must pay a sales tax. Which would save

you more money: To have the tax calculated first or the discount? Explain your

reasoning—be sure to use relevant terminology. In particular, which property of

which operation(s) do you use?

Outline: Build a solution in four steps:

-

(a)

- Use a specific starting price.

-

(b)

- Generalize the process of computing a price after a discount (assuming no

tax).

-

(c)

- Generalize the process of computing a price with tax (assuming no

discount).

-

(d)

- Generalize the two together.

Try a Specific Price. To get started, try a specific starting price, say .

Applying the discount first, the price would be . After the tax, the cost is

.

Now try applying the tax first. The original price with tax would be . Then with

the discount, the cost would be , which is greater thanequal toless

than

the cost when applying the discount first.

Will this work for any starting price? We need to generalize.

Apply a Discount. Suppose the starting price is . A discount, in terms of , will be

. So the price after the discount would . And by the

commutativeinversedistributive

property, this is equal to , or . In other words, rather than computing the discount

and subtracting, we can directly compute the new price by multiplying the original

price by . This makes sense because with a discount of percent, the price we pay will

be percent of the original price.

Apply a Tax. Again, suppose the starting price is .

A tax, in terms of , will be . So the price with tax would . And by the

commutativeidentitydistributive

property, this is equal to . In other words, rather than computing the tax and

adding, we can directly compute the new price by multiplying the original price by .

This makes sense because with a tax of percent, the price we pay after tax will be

percent of the original price.

Apply both. Again, let the starting price be

.

If we apply the discount and then the tax, we multiply first by and then by ,

resulting in the expression .

If, on the other hand, we apply the tax and then the discount, we multiply first by

and then by , resulting in the expression .

These expressions are equal because of the identityassociativedistributive

and commutativeinversedistributive

properties of additionsubtractionmultiplicationdivision

. Thus, the final cost is the same either way.

Money Bags Jon likes to give a tip of % when he is at restaurants. He does this by

dividing his bill by and then doubling it. Explain why this works.

Because is the

same as of the bill, and is twice that.

Regular Reggie likes to give a tip of % when he is at restaurants. He does this by

dividing his bill by and then adding half more to this number. Explain why this

works.

Because is the same as of the bill, is half that, and is the same as

.

Wacky Wally has a strange way of giving tips when he is at restaurants. He does this

by rounding his bill up to the nearest multiple of and then taking the quotient

(when that new number is divided by ). Explain why this isn’t as wacky as

it might sound.

If the bill is already a multiple of , then of the bill is

about , which is slightly less than a standard tip of . By rounding up to the

nearest multiple of 7, the tip will alway be at least and usually slightly

more.