We introduce Stokes’ theorem.

Our final fundamental theorem of calculus is Stokes’ theorem. Historically

speaking, Stokes’ theorem was discovered after both Green’s theorem and the

divergence theorem. Its application is probably the most obscure, with the

primary applications being rooted in electricity-and-magnetism and fluid

dynamics.

Nevertheless, once we know Stokes’ theorem, we can view it as a direct generalization

of Green’s theorem.

Stokes’ Theorem If the components of

\(\vec {F}:\R ^3\to \R ^3\) have continuous partial derivatives and

\(\partial R\) is a

boundary of a closed surface

\(R\) and

\(\vec {p}(t)\) parameterizes

\(\partial R\) in a counterclockwise direction

with the interior on the left, then:

\[ \iint _R (\curl \vec {F})\dotp \uvec {n}\d S = \oint _{\partial R} \vec {F}\dotp \d \vec {p} \]

If we compare the conclusion of Stokes’ theorem to the conclusion of Green’s theorem,

we see that they are quite similar:

\[ \underbrace {\iint _R \curl \vec {F}\d A = \oint _{\partial R} \vec {F}\dotp \d \vec {p}}_{\text {Green's Theorem}}\qquad \underbrace {\iint _R (\curl \vec {F})\dotp \uvec {n}\d S = \oint _{\partial R} \vec {F}\dotp \d \vec {p}}_{\text {Stokes' Theorem}} \]

Like Green’s theorem, Stokes’ theorem computes

circulation along a surface:

In essence, Green’s theorem is nothing more

than Stokes’ theorem when we assume that the surface is restricted to the

\((x,y)\)-plane.

Like the divergence theorem, one application of Stokes’ theorem is to transform a

difficult integral into an easier one.

Consider the line integral

\[ \oint _C (x-y)\d x +(x-2y+z) \d y + (3x+z) \d z \]

where

\(C\) is parameterized by

\(\vec {p}(t) = \vector {\cos (t),\sin (t),3}\),

\(0\le t<2\pi \). Compute this integral

using Stokes’ theorem.

Let

\(R\) be the surface bounded by

\(C\), so in this case

\(C = \partial R\).

Moreover, set

\[ \vec {F}(x,y,z) = \vector {x-y,x-2y+z,3x+z}. \]

Now we may write:

\[ \oint _C (x-y)\d x +(x-2y+z) \d y + (3x+z) \d z = \oint _{\partial R} \vec {F}\dotp \d \vec {p} \]

and Stokes’ theorem says:

\[ \oint _{\partial R} \vec {F}\dotp \d \vec {p} = \iint _R (\curl \vec {F})\dotp \uvec {n}\d S \]

Write with me,

\begin{align*} \curl F(x,y,z) = \vector {\answer [given]{-1},\answer [given]{-3},\answer [given]{2}}\\ \uvec {n} = \vector {\answer [given]{0},\answer [given]{0},\answer [given]{1}}. \end{align*}

Hence

\[ \iint _R \vector {-1,-3,2}\dotp \vector {0,0,1}\d S = \answer [given]{2}\iint _R \d S \]

but

\[ \iint _R \d S = \answer [given]{\pi } \]

Hence

\[ \oint _C (x-y)\d x +(x-2y+z) \d y + (3x+z) \d z =\answer [given]{2\pi }. \]

2 Swapping surfaces

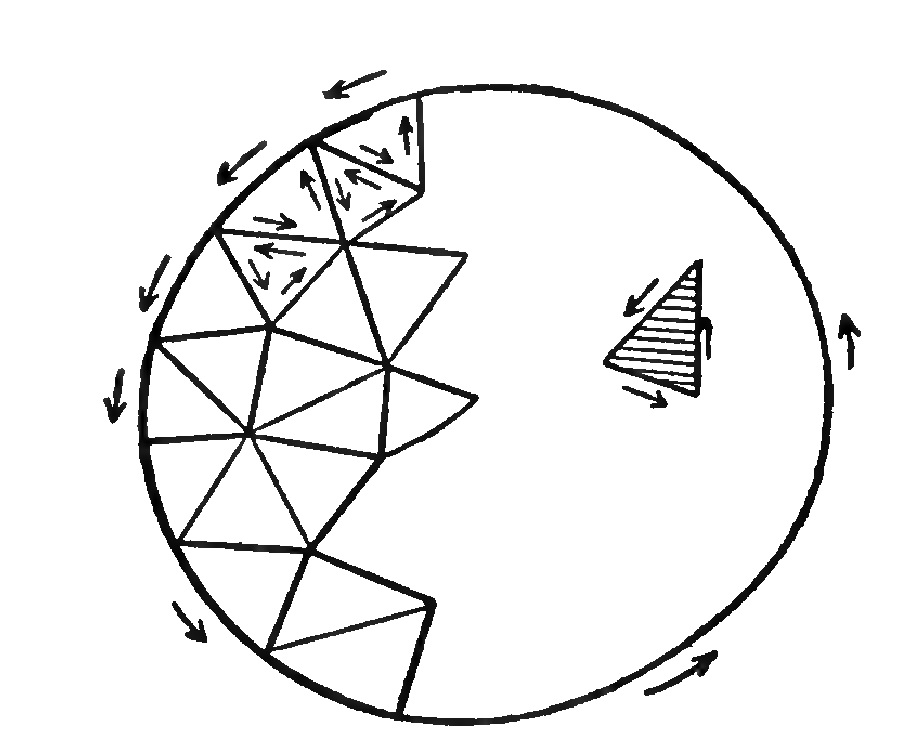

Since Stokes’ theorem says that if we want to evaluate the circulation along a surface,

we need only look at the boundary, and we can sometimes be very clever and swap

one surface for another, provided that they have the same boundary! Consider the

pictures below:

Above we see a region \(R\) on the left and a region \(D\) on the right. In the middle is the

boundary of both regions. Since both regions \(R\) and \(D\) have the same boundary, we

can effectively swap surfaces by using Stokes’ Theorem. Check out the next

example.

Consider the surface integral

\[ \iint _R (\curl \vec {F})\dotp \uvec {n}\d S \]

where

\[ \vec {F}(x,y,z) = \vector {-y,0,z^2} \]

and

\(R\) is the upper hemisphere of the sphere:

\[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 9 \]

Compute this integral using Stokes’ theorem.

Note that the boundary of the sphere is

identical to the boundary of the disk

\[ \vec {p}(t) = \vector {3\cos (t),3\sin (t),0} \]

where

\(0\le t<2\pi \). Hence we may dispense with our

“upper hemisphere” and simply work with the disk of radius

\(3\). Write with me,

\[ \curl F(x,y,z) = \vector {\answer [given]{0},\answer [given]{0},\answer [given]{1}} \]

Hence

\begin{align*} \iint _R \vector {0,0,1}\dotp \vector {0,0,1}\d S &= \iint _R \d S\\ &=\answer [given]{9\pi }. \end{align*}

By Stokes’ theorem this is equal to the integral we desire.

3 Our final fundamental theorem of calculus

How is Stokes’ Theorem a fundamental theorem of calculus? Well consider this:

Are there no more fundamental theorems of calculus? Well, there are, but as you will

see if you continue your study of mathematics, they are all generalizations of the

theorems we already know.

For some interesting extra reading check out: